Early and appropriate imaging reduces delays in revascularization, thereby lowering mortality (3). AMI can be either occlusive or non-occlusive, with the primary aetiology divided as follows: mesenteric artery embolism (50%), mesenteric artery thrombosis (15-25%), and mesenteric venous thrombosis (MVT) (5-15%) (4,5). Thrombosis is usually caused by a combination of stagnant blood flow, hypercoagulability, and endothelial damage (Virchow's triad). Risk factors for MVT include portal hypertension with venous thromboembolism, oral contraceptives, oestrogen replacement therapy, and pancreatitis (7). Internal hernias, for example, after gastric bypass surgery (11), or rarely congenital, can lead to ischaemia through strangulation (12). In patients under 40 years of age, 36% of MVT cases occur without an obvious cause (6).

History, Status, and Findings

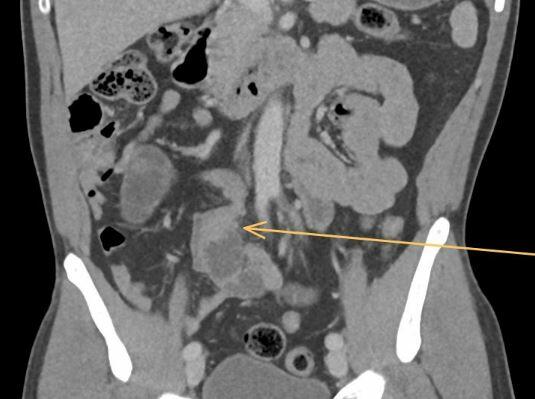

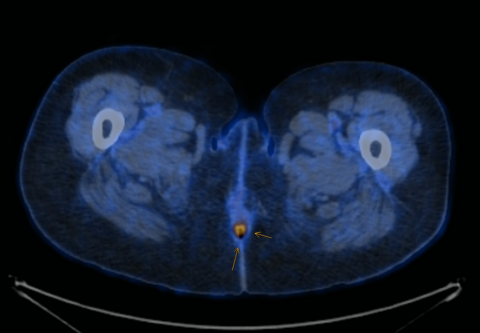

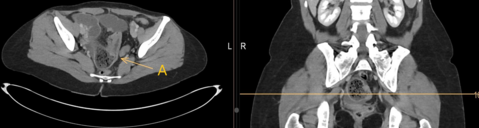

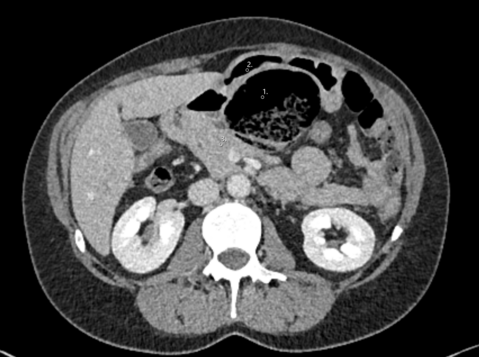

A 49-year-old patient was referred for emergency treatment via the REGA due to severe exacerbation of lower abdominal pain that had persisted for several days. Upon transfer, the patient was hemodynamically and respiratorily stable, and afebrile. On physical examination, diffuse tenderness was noted in the lower abdomen with a maximum tenderness located on the right side. Laboratory tests showed no abnormalities. The patient had no comorbidities and was not taking any regular medication. A CT scan of the abdomen with intravenous contrast revealed a calibre change in the small bowel with signs of venous congestion, raising suspicion of an internal hernia. No signs of free fluid or air were detected. Based on the clinical and radiological findings, we decided to proceed with diagnostic laparoscopy.

Intraoperative Findings

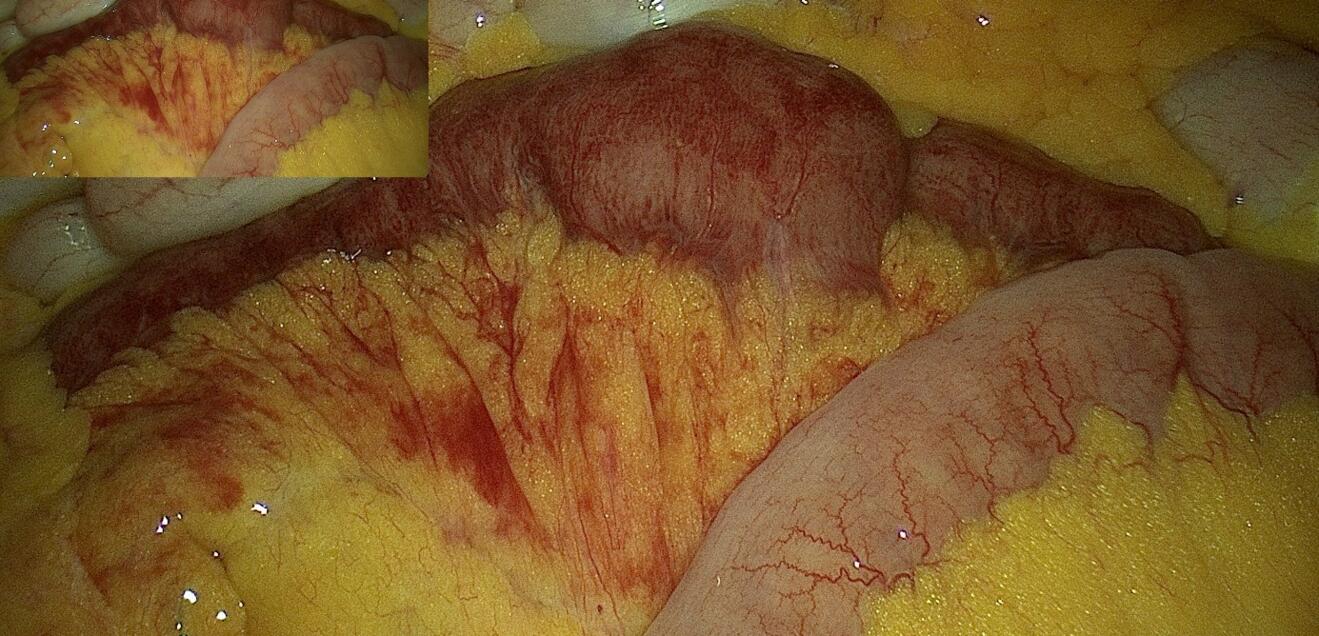

Intraoperatively, approximately 180 cm from the ileocecal valve, a 25 cm long segment of hyperaemic small bowel with the typical tapering pattern towards the mesenteric root, characteristic of MVT, was identified. Due to the absence of necrosis and active peristalsis in the affected segment, we refrained from performing a segmental resection or thrombectomy. A precise inspection of the entire small bowel revealed no internal hernia.

Therapy and Course

Postoperatively, therapeutic heparinization was initiated. The patient recovered well, with good tolerance of oral intake, and bowel passage returned promptly. The preoperatively placed nasogastric tube was removed on the second postoperative day. Due to the favourable clinical course, the patient was discharged in good general condition after a total hospital stay of five days. The cause of the thrombosis could not be determined during the hospital stay. An ECG ruled out atrial fibrillation, and abdominal ultrasound did not reveal any liver or kidney pathology or portal vein thrombosis. Laboratory coagulation test were within normal limits. Additionally, the patient's medical history indicated a healthy lifestyle with a high level of activity and no history of substance abuse.

Four months after hospital discharge, the patient was referred to haematology for evaluation of thrombophilia and haemostatic assessment. No hereditary or acquired thrombophilia were detected, and anticoagulation with Xarelto was discontinued. Ultimately, the cause of the MVT remained unknown. The colleagues from haematology postulated that a temporary internal hernia with resulting venous congestion could have caused the short-range MVT.

Discussion

MVT is a rare but serious surgical emergency that can occur without predisposing factors. In 5-15% of all cases of acute mesenteric ischaemia, acute MVT is the cause (8). Awareness of the condition and prompt diagnosis via CT scan with both arterial and portal venous phases reduces the time to revascularization. Treatment is interdisciplinary and individualized based on the findings of CT angiography.

In case of suspected intestinal ischemia on imaging, diagnostic laparoscopy is indicated. During diagnostic laparoscopy, any internal hernias can be resolved, and the viability of the bowel can be assessed. If there is clinical evidence of severe peritonitis, exploratory laparotomy is indicated. Transmural small bowel necrosis should be resected, and a staged approach with a second-look procedure and concurrent anastomosis is possible. Intravenous fractionated heparin should be initiated postoperatively (9).

In the absence of signs of bowel infarction on imaging or during diagnostic laparoscopy, oral anticoagulation is the treatment of choice. In individual cases, endovascular recanalization may be performed by interventional radiology (8).

In patients with severe abdominal pain without physical findings, MVT should be considered as a differential diagnosis. Particularly in individuals with a personal or family history of deep vein thrombosis or other thromboembolic diseases, MVT should be ruled out promptly when severe abdominal pain is present (10).

Overall mortality rates have decreased over time due to faster diagnosis through improved imaging techniques. The most common causes of death in patients with MVT are sepsis, pulmonary artery embolism, and recurrent thrombosis. Literature reports a 30-day mortality rate of up to 32%. Delayed treatment initiation, more than 24 hours after the onset of symptoms, results in a mortality rate between 80-100% (10).

Summary for Clinical Practice

MVT is a rare emergency. In 5-15% of cases, it is the cause of acute mesenteric ischaemia.

The gold standard for diagnosis is contrast-enhanced CT scan, although peripheral thrombosis of small veins can be difficult to detect.

Treatment is based on clinical and imaging findings, requiring interdisciplinary collaboration.

In suspected intestinal ischaemia, diagnostic laparoscopy/laparotomy is indicated.

Haematological evaluation is recommended for further investigation. Oral anticoagulation is the conservative management approach.