Small bowel obstruction (SBO) constitutes 12–16% of emergency surgical presentations and 20% of emergency operations1. In patients with a prior surgical history, postoperative adhesions are the main cause (65%)2. Conversely, in patients without prior surgical history, the etiology is often more elusive and challenging to identify.

Case report:

A 35-year-old afebrile and cardiopulmonary stable female presented to the emergency department with colicky abdominal pain accompanied by nausea and repeated vomiting over several hours. On physical examination, high-pitched bowel sounds were heard diffusely, with localized tenderness in the right lower abdomen. Laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis (14 G/L) with a normal C-reactive protein (CRP) level. The patient’s medical history was significant only for two cesarean sections. An abdominal ultrasound demonstrated dilated small bowel loops. Following basic analgesia in the emergency department, the patient reported partial improvement in her pain, though it remained present.

Question:

Which of the following represents the most appropriate next step in the management of this patient?

- Abdominal CT scan

- Hospitalization with p.o. contrast-enhanced serial abdominal X-rays

- Diagnostic laparoscopy

- Watchful waiting with outpatient follow-up

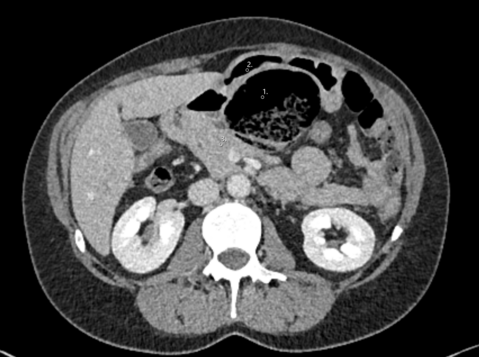

The history of emesis, high-pitched bowel sounds, and dilated small bowel loops on ultrasound strongly suggests SBO. In such cases, particularly when pain persists despite basic analgesia, it is critical to promptly identify the exact cause of the obstruction. Adhesions, likely related to the patient’s prior cesarean sections, are the most common etiology. However, other potential causes, such as hernias, neoplasms, or other intra-abdominal pathologies, must be excluded. While contrast-enhanced serial abdominal X-rays provide dynamic information on contrast passage through the gastrointestinal tract, they lack the sensitivity to accurately identify the cause of SBO. Instead, abdominal CT imaging with intravenous and oral water-soluble contrast is considered the gold standard for diagnosis3,4. A CT scan not only confirms the presence and level of obstruction but also evaluates for complications such as ischemia, strangulation, or perforation. Additionally, CT imaging can identify less common causes of ileus, including intestinal neoplasia (e.g., gastrointestinal stromal tumors [GIST], 5–10%), vascular etiologies (5%), or gallstone ileus (1–4%)5. In this case, an abdominal CT scan revealed SBO characterized by a caliber change in the right lower abdomen and the presence of the small bowel feces sign in the terminal ileum, but no clear etiology for the obstruction was identified. Given the inability to establish a definitive diagnosis noninvasively, a diagnostic laparoscopy was performed. While diagnostic laparoscopy is typically not a first-line diagnostic modality in stable patients, it was deemed necessary in this instance to further evaluate and manage the cause of the obstruction.

Correct answer: A

Intraoperative Findings:

Intraoperatively, a dilated Meckel`s diverticulum containing an impacted fecolith and downstream collapsed small bowel loops were identified approximately 70 cm from the ileocecal valve. Laparoscopic resolution of the obstruction was deemed unfeasible due to the risk of intestinal wall injury. Consequently, a mini-laparotomy was performed, allowing exteriorization of the affected bowel segment. The obstruction was manually relieved, and the diverticulum was excised via transverse resection using a linear stapler (diverticulectomy).

Discussion:

With a prevalence of 2-4%, Meckel`s diverticulum is the most common congenital malformation of the gastrointestinal tract6. First mentioned in 1598, Meckel`s diverticulum is a remnant of the omphaloenteric duct, which connects the yolk sac to the intestinal tube of the embryo7. Normally, this structure obliterates around the seventh week of pregnancy. Since all wall layers of the intestine are present in Meckel`s diverticulum, it is classified as a “true” or “traction” diverticulum. Anatomically, it is typically located approximately 60 cm from the ileocecal valve and is supplied by a branch of the superior mesenteric artery. On its own, Meckel`s diverticulum has no pathological significance and usually (about 80% of cases) remains asymptomatic8. The incidence of complications associated with Meckel`s diverticulum is reported in the literature to range from 4% to 16%. The most common complications in adults include mechanical ileus (14-53%), ulceration (<4%), and, rarely, diverticulitis with perforation9. However, SBO caused by Meckel`s diverticulum is rarely described in the literature, particularly in patients without a history of prior surgery. As The Meckel`s diverticulum remains challenging to detect on imaging, it is frequently underestimated. In the literature there’s no guidelines regarding the management of patients with SBO due to Meckel`s diverticulum. However, studies in patients with SBO with all aetiology showed that the risk of bowel resection under conservative management increases to approximately 30%10, making surgical intervention the preferred treatment approach. Due to the presumed lower stenosis rate, stapled diverticulectomy in a transverse direction to the intestine has become the preferred option. Before resection, it is important to palpate the lesion well to exclude possible ectopic gastric mucosa tissue within the diverticulum. Since the presence of ectopic tissue seems to increase the risk of bleeding and perforation of the diverticulum, classic segmentectomy shoud be considered in those cases11.

Regarding the management of asymptomatic, incidental finding of Meckel`s diverticulum, current guidelines can be found on «UpToDate». According to these guidelines, asymptomatic Meckel`s diverticulum should only be resected if there are palpable abnormalities or corresponding risk factors (male sex, associated adhesions, diverticulum >2cm, patient <18 years)9,12-15. As these guidelines are based on low-quality evidence (observational studies, unsystematic clinical observations or randomized trials with serious deficiencies), the management of asymptomatic Meckel`s diverticulum will remain the subject of controversial discussions.

Summary for clinical practice

- Mechanical ileus resulting from a Meckel`s diverticulum is often underestimated and can be challenging to diagnose through imaging studies.

- In patients presenting with signs of complete ileus, diagnostic laparoscopy with bowel exploration is recommended10.

- A laparoscopic approach is generally preferred; however, laparotomy may be necessary in the management of complications associated with Meckel`s diverticulum.

- Meckel`s diverticulum can be resected transversely (diverticulectomy)13 using a linear stapler or removed via classic segmentectomy.

- Millet I, Ruyer A, Alili C, et al Adhesive small‐bowel obstruction: Value of CT in identifying findings associated with the effectiveness of nonsurgical treatment. Radiology 2014; 273: 425–32

- Rami Reddy SR, Cappell MS. A systematic review of the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of small bowel obstruction. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2017; 19: 1–14

- Suri S, Gupta S, Sudhakar PJ, Venkataramu NK, Sood B, Wig JD: Comparative evaluation of plain films, ultrasound and CT in the diagnosis of intestinal obstruction. Acta Radiol 1999; 40: 422–8

- Gastroenterologie up2date 2022; 18(01): 51-67

DOI: 10.1055/a-1355-0474 - Gallstone ileus: an overview of the literature. Ploneda-Valencia CF, Gallo-Morales M, Rinchon C, et al. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (English Edition) 2017;82:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.rgmx.2016.07.006

- SAGAR J, KUMAR V, SHAH DK. Meckel’s diverticulum: a systematic review. J. R. Soc. Med., 2006, 99(10) : 501-5

- Meckel JF. Uber die divertikel am darmkanal. Arch Physiol 1809; 9:421–53

- Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. Munich: Zuckschwerdt; 2001

- Sagar J, Kumar V, Shah DK. Meckel's diverticulum: a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2006 Oct;99(10):501-5. doi: 10.1177/014107680609901011. Erratum in: J R Soc Med. 2007 Feb;100(2):69. PMID: 17021300; PMCID: PMC1592061

- Leung AM, Vu H: Factors predicting need for and delay in surgery in small bowel obstruction. Am Surg 2012; 78: 403–7

- Ding Y, Zhou Y, Ji Z, Zhang J, Wang Q. Laparoscopic management of perforated Meckel's diverticulum in adults. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9(3):243-7. doi: 10.7150/ijms.4170. Epub 2012 May 4. PMID: 22577339; PMCID: PMC3348529

- Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Senthilkumar R, Madankumar MV, Kavalakat AJ. Laparoscopic management of symptomatic Meckel's diverticula: a simple tangential stapler excision. JSLS. 2008 Jan-Mar;12(1):66-70. PMID: 18402742; PMCID: PMC3016022

- Park JJ, Wolff BG, Tollefson MK, Walsh EE, Larson DR. Meckel diverticulum: the Mayo Clinic experience with 1476 patients (1950-2002). Ann Surg. 2005;241(3):529

- Zani A, Eaton S, Rees CM, Pierro A. Incidentally detected Meckel diverticulum: to resect or not to resect? Ann Surg. 2008;247(2):276

- Bani-Hani KE, Shatnawi NJ. Meckel's diverticulum: comparison of incidental and symptomatic cases. World J Surg. 2004 Sep;28(9):917-20