Bernhard and Lydia Widmann (Surgeon and Intensive Care Nurse) have been based with their 3 children at Nkhoma Hospital, Malawi since 2022. Their focus is on training Malawian surgeons and nurses and building the newly founded surgical department. Before moving to Malawi, they trained and worked at the Kantonsspital St. Gallen, Switzerland.

Malawi’s public health system is free of charge. In 2021, per capita health expenditure was 47 USD, of which 62% was funded by foreign aid.4 The public system offers basic surgical care in 25 district hospitals that are run by non-specialized medical doctors and clinical officers. Fully trained surgeons are only available in the 4 central hospitals. In comparison, Switzerland has about 280 hospitals and a per capita health expenditure of 10´897 USD (factor 232).

Malawi’s surgeons are faced with a nearly impossible task. In 2022, two general surgeons at the Kamuzu Central Hospital in Lilongwe covered a catchment area of 8 million people in Malawi’s central region. The elective procedures are often canceled, due to pending emergencies. Low staffing resources are just one of the challenges. Shortages of essential equipment like gloves, gauze, disinfectants, blood, antibiotics, and analgesics occur daily.

Alongside the public health system, the Christian Health Association of Malawi (CHAM) provides 37% of Malawi’s health care services. Although CHAM facilities are partially funded by the government and international donors, patients need to cover part of the costs, which is usually paid out of pocket. An exploratory laparotomy including anesthesia and perioperative care costs ~150 USD. Most of the rural population cannot afford this amount, even with the support of the extended family.

Despite these challenges, Malawi’s health care is improving. Life-expectancy increased from 46.7 to 66 years in the past 20 years.5 This improvement shows the resilience and ability of the Malawian health workers to provide care despite the lack of resources.

Starting Surgical Care and Training at Nkhoma Hospital

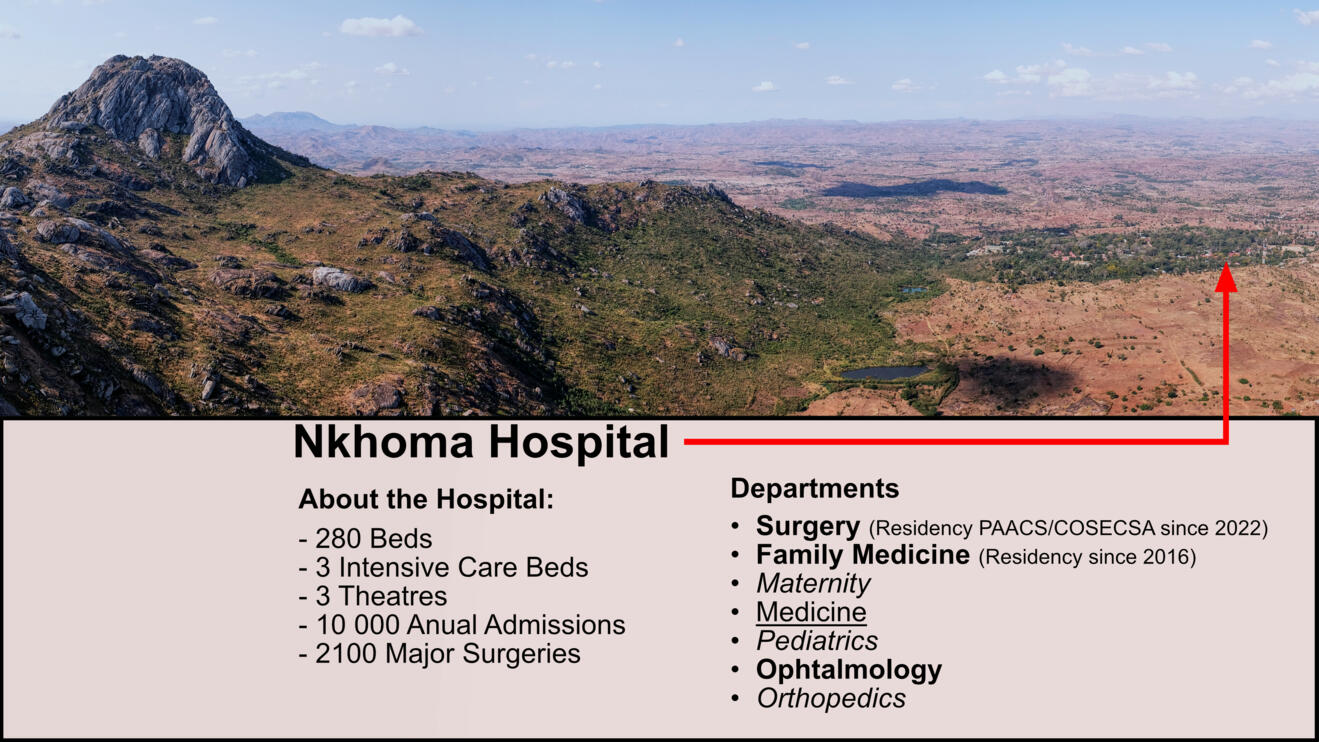

Nkhoma Mission Hospital (Figure 1) is a CHAM hospital 50 km east of Malawi’s capital, Lilongwe. The hospital has had a general surgeon since 2019 and started a 5-year surgical residency program in 2022 (Figure 2). The hospital’s goal is to transition from a district hospital to a teaching and referral hospital. Offering specialized surgical care requires winning over both patients and health providers to accept and provide surgical care.

Winning Patients to Accept Surgical Care

The backbone of Malawi’s health care is carried out by clinical officers with a 3-year training after high school. Clinical officers or nurses can specialize with an 18-month training to perform anesthesia or surgeries. The general population hardly has access to surgical care by specialized surgeons. Many still associate a surgery with poor and often fatal outcomes. Winning trust to undergo surgery means providing safe, accessible, and affordable care.

The impact of old traditions cannot be underestimated. More than 80% of Malawians believe in witchcraft. Many still visit a traditional healer or “witchdoctor” before they approach a health facility (Figure 3). There is the belief that diseases caused by witchcraft can only be cured by witchcraft. Therefore, it is not surprising that patients visit both medical facilities and traditional healers. This often contributes to patients presenting very late. Relatively simple conditions like typhoid fever become major challenges when patients present weeks after the onset of symptoms or with week‑old perforations.

Transportation and financial concerns are another reason for patients not seeking care. Frequently, patients cannot afford the 2-4 $ transport cost to the hospital. Others choose to walk home for 20km after an inguinal hernia repair the day after surgery to avoid paying for transport. Catastrophic health expenditure is a common problem. Waiting lists in the public system are too long, and if the whole family lives on less than $ 500 a year, a hospital bill of $150 is impossible to pay. Patients at Nkhoma Hospital used to sell their farms or their livestock to undergo surgery. If they faced a complication there was nothing left to pay for further care.

To fight catastrophic health expenditure, Nkhoma started a fund for poor patients. Today we can offer every patient who needs surgery an operation regardless of their financial situation. This was made possible by the Mercy-Fund which is mainly funded by the Noemi-Rusch-Stiftung from St. Gallen, Switzerland (https://www.noemiruschstiftung.ch).6 With about $100 per patient, over 400 patients underwent surgery within the last 14 months.

Without foreign aid, surgical care for Malawi’s rural population is currently not possible. Programs like the Mercy-Fund are effective measures to avoid catastrophic health expenditure. A sustainable solution for Malawi’s health system is yet to be found. The available health insurance costs $ 4/month/person which is too much for most Malawians.

Winning Health Workers to Provide Surgical Care

Few Malawian health professionals have seen what modern medicine can do. Not having reliable diagnostic and treatment options means you are flying blind or following plan B in many situations. This has a high impact on working morale, professional learning, and quality improvement. Looking at high-resource settings to learn is often not applicable. High-resource solutions do not necessarily work in a low-resource environment. With many services like emergency endoscopy, interventional radiology, or ERCP not being available in Malawi, many aspects of modern medicine are out of reach. Even a CT-Scan is difficult to attain. Nevertheless, low-resource settings can stimulate improvisation and out-of-the-box thinking with good results. Finding low-resource solutions to solve low-resource setting problems is key.

The main challenge in improving surgical care in Malawi is winning health workers to use the resources that are available. Many lives could be saved if the resources available were used in a timely and appropriate manner.

Increasing resource-limited but evidence-based care is crucial to build motivation, confidence, and hope for the Malawian health system.

At Nkhoma, recent developments have helped not only improve care but also prove that a higher level of care is possible.

With the opening of our 3-bed Intensive Care Unit (ICU) (Figure 4), we are successfully treating patients who previously had no chance of survival. Previously, most patients needing ICU care would either die in the hospital or during/after referral. Being able to effectively help patients is the cornerstone of winning and motivating health workers, but getting things started often needs external expertise.

Another example is laparoscopic surgery. In most African settings, especially in Malawi, laparoscopy is considered too complex and expensive. In October 2022, the first laparoscopic procedure was performed at Nkhoma hospital. Organizing donated laparoscopic equipment involves some effort but it is usually not too difficult to come by. Getting started was a challenge. Most of the theatre staff have not even seen laparoscopic surgery before and essential drugs like muscle relaxants were not available. Today we offer elective and emergency laparoscopy and have started training our residents. Experiencing that change is possible and can happen today helps winning health providers to offer better care.

Conclusion

Safe, accessible, and affordable surgical care for all Malawians will require decades of development. Malawi’s surgical care is still at the beginning, but care is improving day by day.

Acknowledgements

Much of our work in Malawi would not be possible without the support of international donors. Thanks to the Noemi Rusch Stiftung in St. Gallen we do not have to turn down patients for financial reasons. Donations to the Mercy-Fund can be made through the Noemi Rusch Stiftung and are tax exempt for Swiss donors.

Noemi Rusch Stiftung, St. Gallen

Credit Suisse (Schweiz) AG

IBAN: CH95 0483 51269503 1100 0

BIC / SWIFT: CRESCHZZ80A

Clearingnummer: 4835

Reference: Malawi Mercy-Fund

- Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L, et al. Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. The Lancet. 2015;386:569–624.

- O’Flynn E, Andrew J, Hutch A, et al. The Specialist Surgeon Workforce in East, Central and Southern Africa: A Situation Analysis. World j surg. 2016;40:2620–2627.

- Varela C, Young S, Groen R, et al. Untreated surgical conditions in Malawi: A randomised cross-sectional nationwide household survey. Mal Med J. 2017;29:231.

- WHO. Global Health Expenditure Database Available from: https://apps.who.int/nha/database/. Accessed March 14, 2024.

- Gapminder. Available from: https://www.gapminder.org/. Accessed March 14, 2024.

- Noemi Rusch Stiftung. Available from: https://www.noemiruschstiftung.ch.