Case description

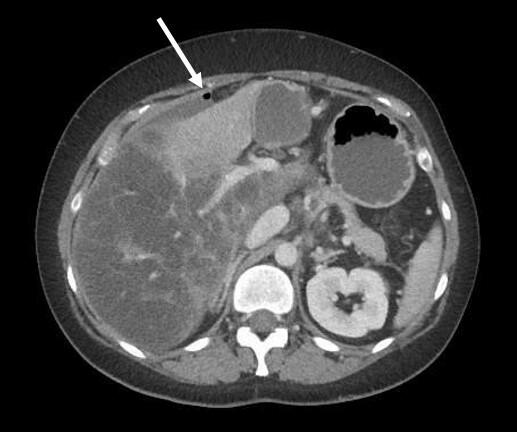

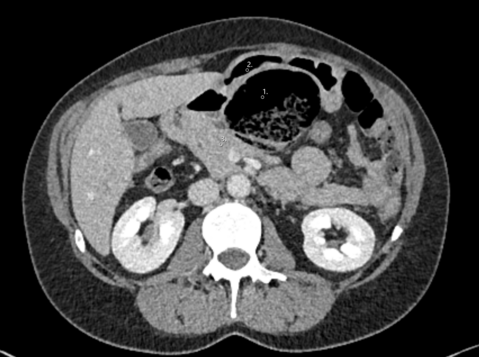

Vital parameters on admission were normal (heart rate 96/min., blood pressure 134/78 mmHg, respiratory rate <22/Min.) the quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score was zero. On physical examination, the abdomen was tender with distension and rebound tenderness in all quadrants. Initial laboratory results showed a mild leucocytosis (10.3G/l) and mildly elevated CRP (30mg/l); elevated liver enzymes (AST 223 U/l, ALT 74U/l, ALP 245U/l, GGT 789 U/l, Bilirubin 51µmol/l), elevated lactate levels (6.9mmol/l) and a decreased factor V (0.50) indicated an acute liver failure. There was a moderate amount of free fluid on ultrasound examination. A CT-scan of the abdomen was performed (Figure 1).

Question: What is the appropriate next step in management of the patient?

- admission to the ICU (intensive care unit) and observation

- antibiotics, diagnostic laparoscopy

- antibiotics, liver work up

- gastroscopy

The correct answer is: B

Case solution

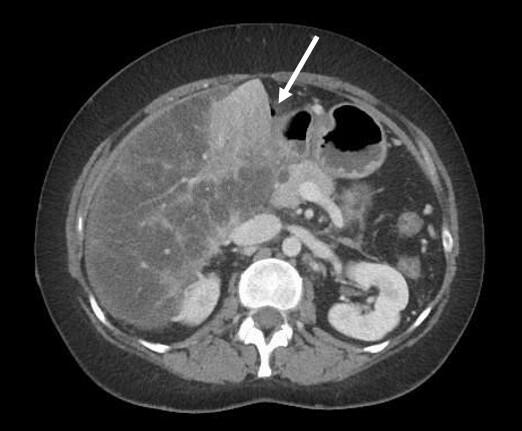

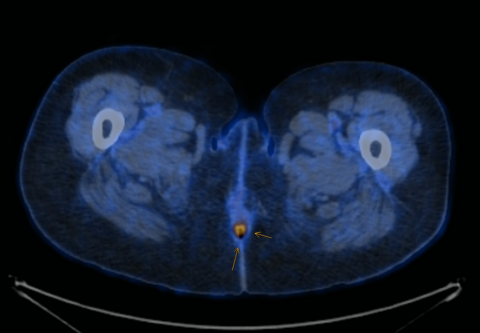

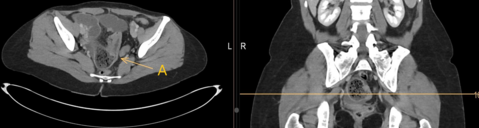

The intravenous-contrast-enhanced CT-scan shows an intestinal perforation with free air around the liver and the gastric antrum, highly suspicious for a perforation of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Ascites, extensive hypodense areas of the liver and spontaneous porto-systemic shunts including esophageal and umbilical varices indicate liver cirrhosis with portal hypertension.

The treatment of gastrointestinal perforation should include stabilization of the patient, antibiotics and source control [1]. In patients with upper gastrointestinal perforation and signs of peritonitis and pneumoperitoneum, surgery should be performed as soon as possible [2]. Diagnostic laparoscopy, lavage and closure of the perforation defect is an effective and safe approach with less postoperative morbidity than open surgery [3]. In the further follow-up, underlying reason for perforation needs to searched e.g. by gastroscopy.

Therefore, the patient received antibiotics (Imipenem-cilastatin 500 mg i.v.), and a diagnostic laparoscopy was performed. We established the pneumoperitoneum via Verres’ needle at the Palmer’s Point and placed three ports carefully avoiding injury to the umbilical varices. We found a fibrinous peritonitis, ascites, a prepyloric gastric perforation as well as an enlarged right liver with a nodular surface (Figure 2). Ascites was collected for microbiological analysis. The gastric perforation was closed by laparoscopic full-thickness sutures, (V-Loc™ 90, 15 cm, 2 suture lines) an intraoperative methylene blue test and test for air-leakage after insufflation via the naso-gastric tube confirmed patency of the suturing. An omental patch was placed on the closed perforation and fixed by a loose suture to stimulate fibrin formation and tissue regeneration [4, 5]. An excisional liver biopsy was obtained to establish the diagnosis of liver cirrhosis. After extensive lavage, two drains were inserted intraabdominally to ensure drainage of ascites.

Discussion

Surgery in patients with acute liver failure is associated with high morbidity and mortality [6, 7]. To ensure close observation and optimal fluid and hemostasis management, the patient was admitted to the ICU postoperatively. After two days the patient was transferred from the ICU to the surgical ward. The naso-gastric tube was removed on the fourth postoperative day and the patient tolerated oral food intake well. Antibiotics were administered for seven days and inflammatory markers declined as well as the slightly elevated liver enzymes. The patient left the hospital on the eighth postoperative day, and the outpatient follow-up examination was scheduled in our hepatology unit.

A gastroscopy six weeks after surgery showed esophageal varices but was unremarkable regarding the gastric perforation. The punch biopsy revealed liver cirrhosis (meta-analysis of histological data in viral hepatitis/METAVIR score F4). It should be noted, that the sensitivity of an intraoperative liver biopsy in patients with macroscopic liver surface abnormalities is limited to 68% [8]. Therefore, further liver work up in patients with laparoscopically suspected liver disease should be considered even if intraoperative liver biopsies are negative.

- Langell JT, Mulvihill SJ (2008) Gastrointestinal Perforation and the Acute Abdomen. Medical Clinics of North America 92:599–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2007.12.004

- Tarasconi A, Coccolini F, Biffl WL, et al (2020) Perforated and bleeding peptic ulcer: WSES guidelines. World J Emerg Surg 15:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-019-0283-9

- Hoshino N, Endo H, Hida K, et al (2022) Laparoscopic Surgery for Acute Diffuse Peritonitis Due to Gastrointestinal Perforation: A Nationwide Epidemiologic Study Using the National Clinical Database. Annals of Gastroent Surgery 6:430–444. https://doi.org/10.1002/ags3.12533

- Turner WW (1988) Perforated Gastric Ulcers: A Plea for Management by Simple Closures. Arch Surg 123:960. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400320046008

- Di Nicola V (2019) Omentum a powerful biological source in regenerative surgery. Regenerative Therapy 11:182–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reth.2019.07.008

- Klein LM, Chang J, Gu W, et al (2020) The Development and Outcome of Acute‐on‐Chronic Liver Failure After Surgical Interventions. Liver Transpl 26:227–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.25675

- Pantea R, Meister P, Neuhaus JP, et al (2021) Chirurgie bei Patienten mit Leberzirrhose. Chirurg 92:838–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00104-020-01319-z

- Poniachik J, Bernstein DE, Reddy KR, et al (1996) The role of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of cirrhosis. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 43:568–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5107(96)70192-X