Case description

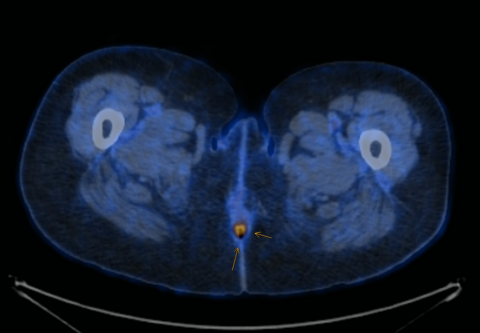

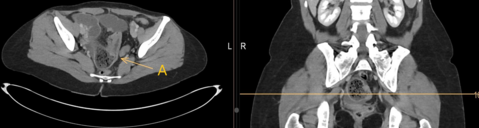

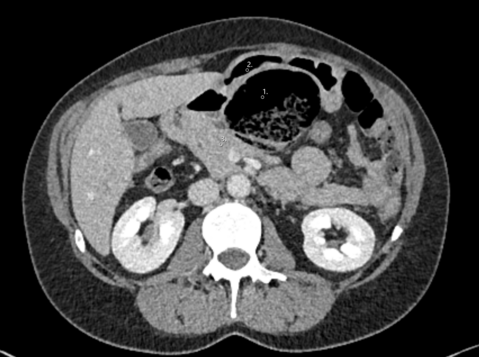

He was taken to a peripheral hospital, where he arrived in hemodynamically stable condition. Initial GCS was 14 due to the inability to recall the event and the abdomen was soft but exhibited diffuse tenderness upon palpation. The remaining physical examination was inconspicuous. Blood exam showed decreased Hemoglobin of 104g/l and slightly increased inflammatory markers (Leucocytes 11.1G/l, CP 24mg/l). Emergent contrast-enhanced trauma CT-scan was performed and showed simultanous undisplaced fractures of the parietal and petrosal bone with epidural and subarachnoidal hematoma on the right hemisphere and a slight midlineshift (Fig. 1A-B) as well as a large retroperitoneal hematoma around the duodenum and pancreas with a pseudoaneurysm of the posterior inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (Fig. 1C-E). The patient was subsequently transferred to our center for further management.

What is the most likely underlying etiology of the above-mentioned sequence of events and current condition of the patient?

1. Chronic pancreatitis

2. Aneurysm of the cerebral arteries

3. Celical trunc stenosis

4. Polyarteritis nodosa

5. Coagulation disorder

Case solution

Spontaneous visceral arterial aneurysms are rare but can be life threatening in cases of rupture1. Pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysms comprise up to 2% of visceral aneurysms2 and can develop due to immunologic arterial diseases (e.g., polyarteritis)3, stenosis/obstruction of celiac vessels (atherosclerosis and median arcuate syndrome)4 or pancreatitis / post pancreatic surgery5.

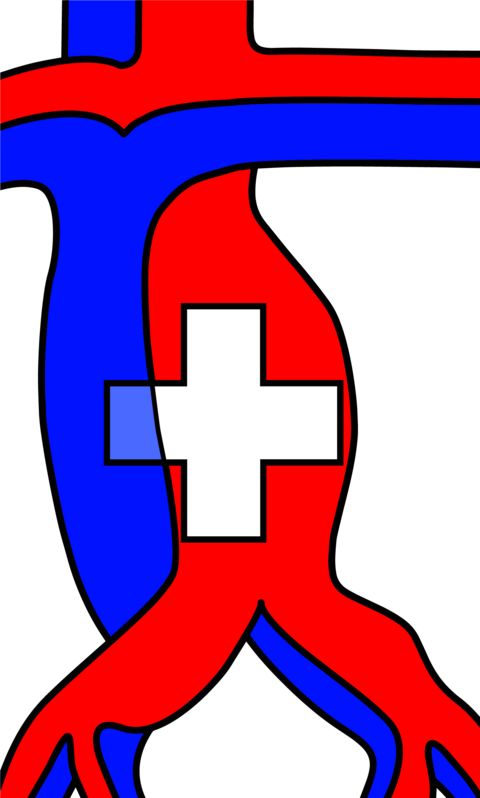

In the current case, the etiology of the abdominal pseudoaneurysm was suspected to be due to atherosclerotic stenosis of the celiac trunk (Fig 2A, red arrow). Indeed, angiography demonstrated flow reversal from the AMS through the pancreaticoduodenal arcade (PDA) containing the aneurysm (Fig. 2B, red circle) towards the gastroduodenal artery and up to the hepatic artery (Fig. 2B, blue arrow), a known risk factor for aneurysm development6. In contrast, no flow into the gastroduodenal artery from the celiac trunk was observed (Fig. 2C, red circle). During angiography, no active bleeding was visible anymore, and an uneventful selective coil-embolization of the inferior posterior PDA was performed (Fig. 2D). The cranial fractures and intracranial hemorrhage were judged to be traumatically due to syncope of the patient due to abdominal pain/blood loss with subsequent head trauma, as no underlying cerebral etiology was diagnosed. The further course of hospitalization was uncomplicated, and the patient discharged home on the 7th hospitalization day. The patient’s follow-up in our surgical outpatient clinic showed a satisfying recovery from the retroperitoneal bleeding, but neurologically there is a persisting mild cognitive impairment, which indicated a stay in a rehabilitation center. Complete re-integration at work is still ongoing.

- Pitton et al. Visceral artery aneurysms: Incidence, management, and outcome analysis in a tertiary care center over one decade. Eur Radiol. 2005; 25:2004–2014

- Pasha et al, Splanchnic artery aneurysms, Mayo Clin Proc. 2007; 82(4):472-9

- Reyes Abon et al, BMJ Case Rep. 2021, Pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm associated with polyarteritis nodosa presenting as massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding. 2021; 19;14(11)

- Stoecker et al. J Vasc Surg. A large series of true pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysms, 2022;75(5):1634-1642

- Walia et al. World J Gastrointest Surg . Vascular complications of chronic pancreatitis and its management. 2023; 15(8): 1574–1590

- Katsura et al. J Gastrointest Surg. True aneurysm of the pancreaticoduodenal arteries: a single institution experience. 2010;14(9):1409-13