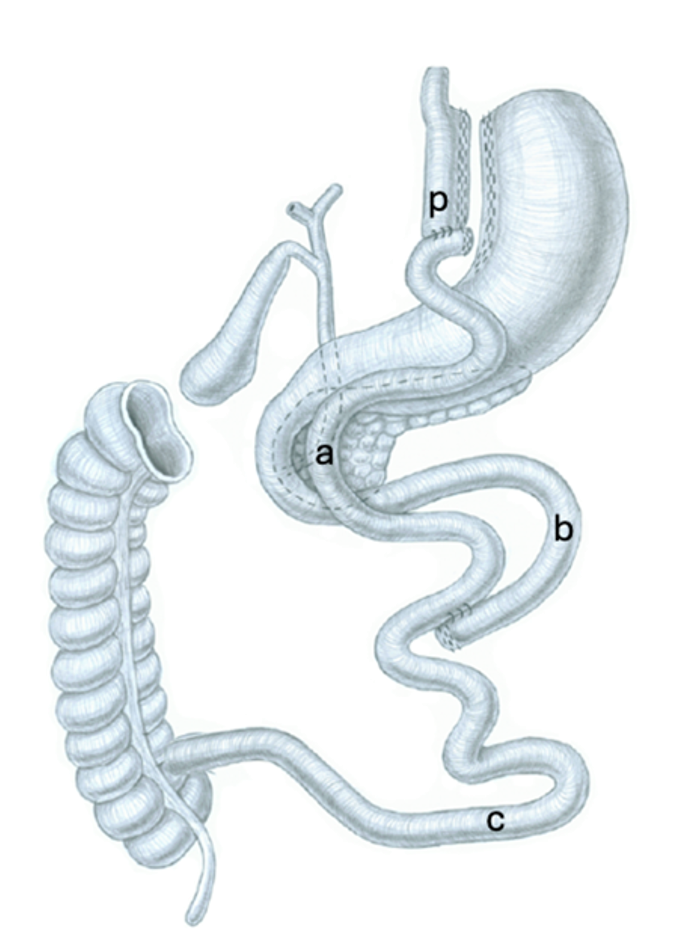

Nowadays, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) involves creating a small pouch along the lesser curvature of the stomach, which can hold between 15 and 30 mL (Figure 1). The jejunum is then divided around 20–80 cm below the Treitz ligament. The divided end of the jejunum is connected to the pouch (Figure 1, p) to form a gastrojejunostomy (GJ). The distal jejunum and the biliopancreatic limb (BPL) (Figure 1, b) are then joined 75–150 cm from the GJ to create a jejunojejunostomy (JJ). The alimentary limb (AL) (Figure 1, a) is the section of the small intestine that carries food from the pouch (GJ) to the point where it joins the BPL at the JJ. The BPL extends from the ligament of Treitz to the JJ and carries bile and pancreatic enzymes from the liver and pancreas, respectively, to the point where it joins the alimentary limb. The common limb (CL) (Figure 1, c), is the segment of the small intestine where the BPL and the AL converge.

As of today, the ideal lengths for the AL, BPL, and CL in RYGB still remain unknown. During a RYGB, surgeons typically use around two meters of the jejunum to create both AL and BPL. While they typically measure the lengths of both the BPL and AL, they usually don't measure the CL (3). However, one important point which should be considered is that the small bowel length ranges from 3.5 to 13 meters. Therefore the CL can range from 2 to 11 meters (4). This difference in CL length could partly explain the different outcomes reported in studies of RYGB.

RYGB was initially thought to mainly work by restricting food intake and reducing nutrient absorption. However, current research suggests it involves a complex mix of mechanisms leading to various metabolic changes. These mechanisms include changes in the gut microbiome, increased levels of certain substances like bile acids in the body and the release of hormones like GLP-1 and PYY (5).

Studies show that the lengths of the BPL, AL, and CL can affect these mechanisms, which in turn can influence weight management and the risk of nutritional deficiencies (6,7).

Searching the optimal RYGB limb lengths

Efforts to optimize outcomes led to explorations of lengthening intestinal segments by shortening others. However, this approach often resulted in complications such as diarrhea and nutrient deficiencies (8–10)

The idea of adjusting RYGB limb lengths has prompted ongoing efforts to find a balance between weight loss and health enhancements while minimizing adverse effects such as nutrient deficiencies.

Numerous studies have investigated the impact of varying pouch and intestinal lengths on weight loss and health outcomes. However, we still lack precise recommendations due to variations in study designs and outcomes assessed (11,12).

Alimentary Limb

The role of the AL in RYGB surgery has been extensively studied to understand its impact on weight loss outcomes. Early research compared AL lengths of 75 cm and 150 cm, revealing that a longer AL contributed to improved weight loss for up to 36 months, although this effect diminished after four years (10). Subsequent investigations examining different AL lengths based on BMI groups, failed to identify significant differences in long-term weight loss outcomes (13). A systematic review suggested limited benefits of extending the AL, particularly for individuals with a BMI over 50 kg/m2 (14).

Moreover, researchers have explored the influence of the total length of the alimentary limb (TALL) on weight loss outcomes by manipulating the length of the BPL showing superior weight loss outcomes in the long BPL group (15,16). The TALL encompasses both the AL and the CL. It's noteworthy that alterations in the BPL or CL can affect the TALL differently for patients. While most RYGB studies do not measure TALL, those that do suggest that reducing the TALL (by lengthening the BPL) may be more critical for promoting weight loss than solely extending the AL. Maintaining a TALL above 400 cm and ensuring a CL length of at least 200 cm is crucial to mitigate potential complications such as protein malnutrition and diarrhea (17).

Biliopancreatic Limb

Scopinaro introduced the biliopancreatic diversion (BPD) technique in 1979, demonstrating its effectiveness in managing conditions like high cholesterol and type 2 diabetes (18). While the BPL in BPD procedures is crucial for success, a short CL (50 – 75cm) can lead to severe malnutrition (19). The duodenal switch BPD addressed this issue with a longer CL (100cm) (20). Studies suggest that RYGB with an extended BPL (Figure 2) may enhance weight loss, though findings on total small bowel length vary (15,21).

A randomized controlled trial comparing RYGB with a long BPL (BPL 150 cm, AL 75 cm) to a short BPL (BPL 75 cm, AL 150 cm) found greater weight loss over four years in the long BPL group (16).

Interestingly, studies comparing different BP limb lengths note elevated GLP-1 cell density in patients with longer BP limbs, suggesting a possible link between BP limb length and postoperative enteroendocrine cell adaptation, contributing to slightly enhanced weight loss and glycemic control in RYGB procedures (12,14).

Our ongoing SLIM trial aims to bridge this knowledge gap by investigating the safety and efficacy of long BPL RYGB (22). It achieves this by comparing two groups, each comprising 400 patients: one with an 80 cm BPL and 180 cm AL, and the other with a 180 cm BPL and 80 cm AL. With this approach we hope to understand how the length of the remaining CL may impact outcomes such as weight loss, resolution of comorbidities, and side effects.

Limb modification for addressing suboptimal weight loss after RYGB

RYGB is known for providing lasting weight loss and improvements in obesity-related conditions. However, up to 35% of patients experience only partial response or recurrent weight gain (defined as BMI > 35 kg/m2 or %WL < 20%) after surgery (23,24). The reasons behind this are multifactorial, making revisional surgery complex with no consensus on the optimal approach. While some revisions, like increasing restriction by modification of gastric pouch or gastrojejunal (GJ) size, yield mixed results, mostly temporarily. Limb modification or distalization has shown promise in enhancing weight loss and alleviating comorbidities. Distalization, which involves shortening the CC by elongating either AL or BPL (Figure 3), has demonstrated significant weight loss benefits, albeit with risks of malabsorption and nutritional deficiencies. Different terms such as "long-limb" or "distal" gastric bypass have been used to describe these revisions, each focusing on different limb modifications to achieve desired outcomes (8,24).

Based on the previously mentioned studies as well as a systematic review and meta-analysis on revision procedures for weight recurrence after RYGB, it seems that shortening the CC and elongating the BPL, results in a better weight loss and improvement in comorbidities over both short and long terms with lower risk of malnutrition compared to lengthening of the AL in our own experience (25)(26). In primary RYGB, according to a systematic review including 21 studies of RYGB, a distalization to at least 200 cm of CC and 400 cm of TALL is recommended to prevent nutritional problems (17).

Patients undergoing RYGB distalization require vigilant management, including regular nutritional monitoring and supplementation. Due to the complexity of interpreting data and the variety of factors influencing outcomes, distalization should be reserved for carefully selected patients (3).

Conclusion

In conclusion, finding the ideal limb length for RYGB involves finding a balance between maximizing weight loss and preventing malnutrition. While RYGB surgery is effective in achieving lasting weight loss, some patients experience suboptimal results or recurrent weight gain over time. Modifying limbs, especially by extending the BPL, holds promise for enhancing weight loss without exacerbating side effects. Thus, careful patient selection and thorough monitoring are essential for optimizing outcomes in RYGB procedures. Further research and refinement of surgical techniques are needed to determine the optimal limb lengths in the individual patient and enhance long-term success in bariatric surgery.

Reviewed by

Sarah Peisl, Moritz Sparn, Editorial Board

- Mason EE, Ito C. Gastric bypass. Ann Surg. 1969 Sep;170(3):329–39.

- Griffen WO, Young VL, Stevenson CC. A prospective comparison of gastric and jejunoileal bypass procedures for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 1977 Oct;186(4):500–9.

- Aleassa EM, Papasavas P, Augustin T, Khorgami Z, Benson-Davies S, Ghiassi S, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery literature review on the effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass limb lengths on outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2023 Jul;19(7):755–62.

- Tacchino RM. Bowel length: measurement, predictors, and impact on bariatric and metabolic surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(2):328–34.

- García-Cañaveras JC, Donato MT, Castell JV, Lahoz A. Targeted profiling of circulating and hepatic bile acids in human, mouse, and rat using a UPLC-MRM-MS-validated method. J Lipid Res. 2012 Oct;53(10):2231–41.

- le Roux CW, Aylwin SJB, Batterham RL, Borg CM, Coyle F, Prasad V, et al. Gut hormone profiles following bariatric surgery favor an anorectic state, facilitate weight loss, and improve metabolic parameters. Ann Surg. 2006 Jan;243(1):108–14.

- Guo Y, Huang ZP, Liu CQ, Qi L, Sheng Y, Zou DJ. Modulation of the gut microbiome: a systematic review of the effect of bariatric surgery. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018 Jan;178(1):43–56.

- Sugerman HJ, Kellum JM, DeMaria EJ. Conversion of proximal to distal gastric bypass for failed gastric bypass for superobesity. J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1(6):517–24; discussion 524-526.

- Torres JC. Why I Prefer Gastric Bypass Distal Roux-en-Y Gastroileostomy. Obes Surg. 1991 Jun;1(2):189–94.

- Brolin RE, Kenler HA, Gorman JH, Cody RP. Long-limb gastric bypass in the superobese. A prospective randomized study. Ann Surg. 1992 Apr;215(4):387–95.

- Gan J, Wang Y, Zhou X. Whether a Short or Long Alimentary Limb Influences Weight Loss in Gastric Bypass: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes Surg. 2018 Nov;28(11):3701–10.

- Zorrilla-Nunez LF, Campbell A, Giambartolomei G, Lo Menzo E, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. The importance of the biliopancreatic limb length in gastric bypass: A systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019 Jan;15(1):43–9.

- Choban PS, Flancbaum L. The effect of Roux limb lengths on outcome after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Obes Surg. 2002 Aug;12(4):540–5.

- Orci L, Chilcott M, Huber O. Short versus long Roux-limb length in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery for the treatment of morbid and super obesity: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Surg. 2011 Jun;21(6):797–804.

- Nergaard BJ, Leifsson BG, Hedenbro J, Gislason H. Gastric bypass with long alimentary limb or long pancreato-biliary limb--long-term results on weight loss, resolution of co-morbidities and metabolic parameters. Obes Surg. 2014 Oct;24(10):1595–602.

- Homan J, Boerboom A, Aarts E, Dogan K, van Laarhoven C, Janssen I, et al. A Longer Biliopancreatic Limb in Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Improves Weight Loss in the First Years After Surgery: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Obes Surg. 2018 Dec;28(12):3744–55.

- Wang A, Poliakin L, Sundaresan N, Vijayanagar V, Abdurakhmanov A, Thompson KJ, et al. The role of total alimentary limb length in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2022 Apr;18(4):555–63.

- Scopinaro N. Biliopancreatic diversion: mechanisms of action and long-term results. Obes Surg. 2006 Jun;16(6):683–9.

- Papadia FS, Adami G, Razzetta A, Florenzano A, Longo G, Rubartelli A, et al. Biliopancreatic diversion for severe obesity: long-term weight maintenance and occurrence of nutritional complications are two facets of the same coin. Br J Surg. 2024 Mar 2;111(3):znae058.

- Hess DS, Hess DW. Biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch. Obes Surg. 1998 Jun;8(3):267–82.

- MacLean LD, Rhode BM, Nohr CW. Long- or short-limb gastric bypass? J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5(5):525–30.

- Kraljević M, Schneider R, Wölnerhanssen B, Bueter M, Delko T, Peterli R. Different limb lengths in gastric bypass surgery: study protocol for a Swiss multicenter randomized controlled trial (SLIM). Trials. 2021 May 19;22(1):352.

- Magro DO, Geloneze B, Delfini R, Pareja BC, Callejas F, Pareja JC. Long-term weight regain after gastric bypass: a 5-year prospective study. Obes Surg. 2008 Jun;18(6):648–51.

- Kermansaravi M, Davarpanah Jazi AH, Shahabi Shahmiri S, Eghbali F, Valizadeh R, Rezvani M. Revision procedures after initial Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, treatment of weight regain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Updates Surg. 2021 Apr;73(2):663–78.

- Kraljević M, Köstler T, Süsstrunk J, Lazaridis II, Taheri A, Zingg U, et al. Revisional Surgery for Insufficient Loss or Regain of Weight After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: Biliopancreatic Limb Length Matters. Obes Surg. 2020 Mar;30(3):804–11.

- Linke K, Schneider R, Gebhart M, Ngo T, Slawik M, Peters T, et al. Outcome of revisional bariatric surgery for insufficient weight loss after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: an observational study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020 Aug;16(8):1052–9.