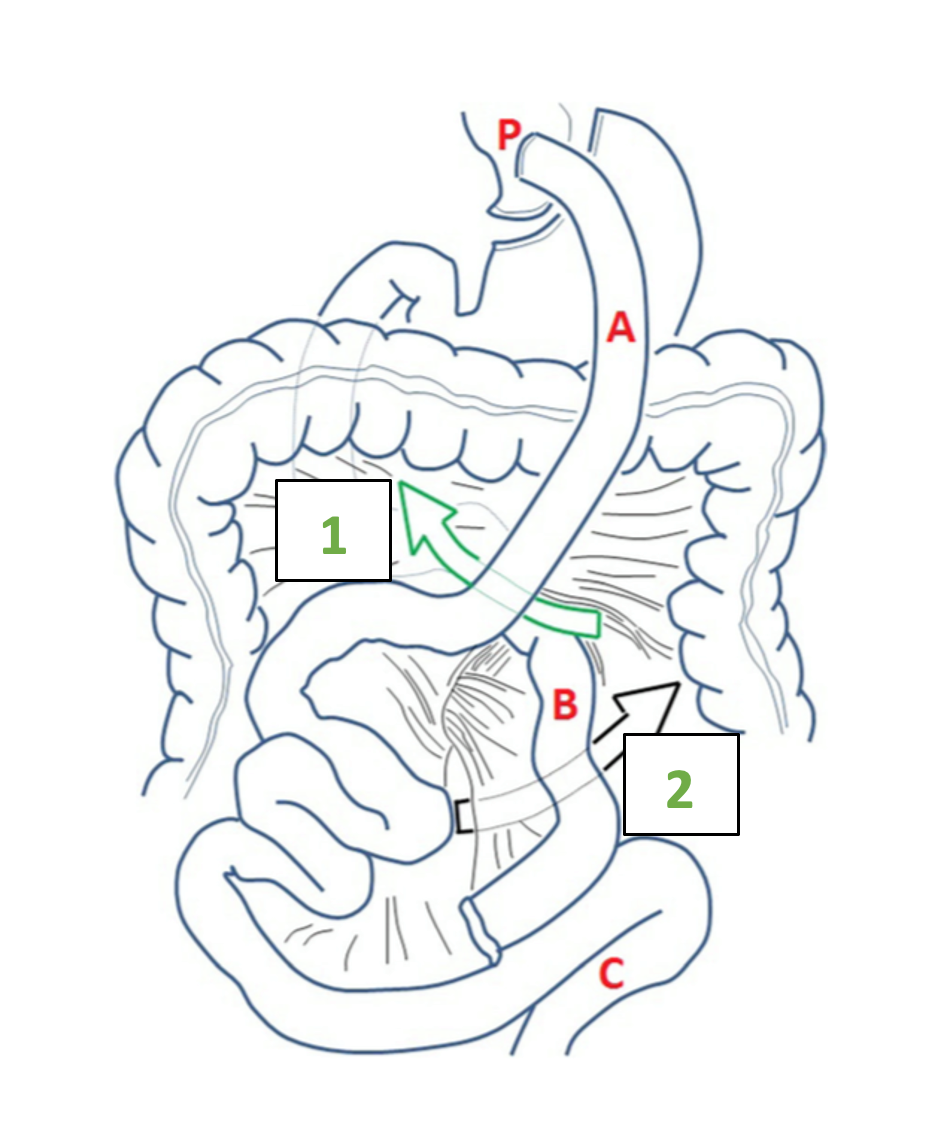

During the RYGB procedure with an antecolic gastro-jejunal anastomosis, two mesenteric defects are surgically created. The first defect is located between the mesentery of the ascending alimentary limb and the mesocolon of the transverse colon. This defect is called the mesenteric-mesocolic or Petersen’s space (Video 1). The second defect is located at the jejuno-jejunostomy and is called the inter-mesenteric space or Brolin space (Figure 1). If the RYGB is created with a retrocolic alimentary limb, herniation of the small bowel can also occur through the defect of the transverse mesocolon (1, 2).

Although the routine closure of the mesenteric defect has significantly reduced its incidence, internal hernia after RYGB still occurs in about 5% of patients;(3) series with long-term follow-up even show cumulative incidences of internal hernia up to 12%.(3) Besides non-closure of the initial mesenteric defect, the main risk factor is increased weight loss.(3) A total weight loss of ≥ 30% is associated with a threefold-higher risk.(4) Internal hernia is usually part of the late complications after RYGB and often occurs two to three years postoperatively at the time of maximal weight loss(5) but can occur any time after the initial operation.

Abdominal pain and nausea or vomiting are common symptoms in patients with RYGB seeking care at the emergency department. The diagnosis of internal hernia can be challenging, especially as there are several differential diagnoses, for instance, gastric ulcer, biliary disease, obstruction at the jejuno-jejunostomy, or a dumping syndrome. Early diagnosis is of paramount importance, as a delay in treatment can lead to bowel necrosis and perforation and may be life-threatening for the patient.

How to handle the diagnosis?

Patients may present with severe acute abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting but may also present with vague intermittent or chronic abdominal pain, as the hernia can be recurrent by nature. Anamnesis should always include the amount of weight loss. If possible, the operating report of the bariatric procedure should be obtained to understand the exact anatomy of the reconstruction and get information about the initial closure of mesenteric defects. The physical examination can range from non-pathological to diffuse peritonism. Laboratory findings might be normal.

Patients with symptoms of acute bowel obstruction and a high clinical suspicion of ischemia or necrosis should undergo direct emergent surgical exploration; however, also patients with more subacute symptoms should undergo further investigations rapidly.

An abdominal CT scan is an important adjunct for the diagnosis of internal hernia.(6, 7)

The probability of an internal hernia increases from 43% to 82.7% in the case of a positive CT scan with the pathological signs for internal hernia and the probability of absence of an internal hernia increases from 57% to 85.8% in the case of a negative scan.(6) Additionally, the CT scan helps to confirm or exclude eventual differential diagnosis.

Various radiological signs on the CT scan may indicate internal hernia: bowel obstruction, venous congestion, mesenteric edema, twisting of the mesenteric vessels (swirl sign), enlarged lymph nodes, clustered intestinal loops, ascites, the mushroom sign (a mushroom-shaped herniation of the mesenteric root), the hurricane eye sign (tubular appearance of the mesenteric fat surrounded by small bowel), or a right-sides anastomosis.(6)

The twisting of the mesenteric vessels (swirl sign), mesenteric edema, and venous congestion seem to be the most accurate radiological predictors(6) (Figure 2).

Even in the presence of one or more radiological signs, an exploratory laparoscopy can be negative, especially in pauci-symptomatic patients.

To further help identify patients who should undergo emergent exploratory laparoscopy,

a predictive model of internal hernia after RYGB was recently developed by Giudicelli et al.(7) The validated model, called the SWELL (swirl, excess weight loss, liquid) score, is based on clinical signs and radiological parameters and can help identify patients with a high probability of internal hernia. The score is based on three parameters, each parameter providing 1 point to the score.

SWELL score:

- Excessive body weight loss of ≥ 95%

- Swirl sign

- Free liquid in one quadrant

Patients with a SWELL score of ≥ 2 have a high probability (60.7%) of an intraoperative confirmation of internal hernia anda low probability (5.9%) of undergoing negative exploratory laparoscopy.

Patients with a high clinical suspicion and a positive CT scan or patients with a SWELL score of ≥ 2, even if pauci-symptomatic, should undergo an emergent exploratory laparoscopy to avoid delayed diagnosis and management.

In patients with a negative CT scan, the risk for the presence of an internal hernia remains approximately 15%.(6) Patients may be kept under observation, and, in the case of persistent abdominal pain and a lack of an alternative diagnosis, exploratory laparoscopy should be considered.

Differential diagnoses to internal hernia after RYGB

The most common alternative diagnoses are marginal ulcers, biliary disease, or obstructions at the jejuno-jejunal anastomosis (stricture, kinking, invagination)(1). Marginal ulcers at the gastro-jejunostomy are often associated with mid-epigastric pain but can also present with nausea or vomiting. The most important risk factors are smoking and intake of nonsteroidal inflammatory drugs. An upper endoscopy remains the standard diagnostic tool and the treatment is based on proton pump inhibitors (1).

Biliary disease can present as biliary colic with post-prandial crampy epigastric or right-upper quadrant pain and nausea or vomiting or with persistent abdominal pain and even fever in the presence of acute cholecystitis. Laboratory findings might show elevated liver enzymes. The diagnosis is typically made by abdominal ultrasound. The management of biliary disease is similar to that of patients with no RYGB, with the exception of choledocholithiasis, which needs special consideration, as the anatomy of the RYGB does not allow for standard endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (8).

Obstructions at the jejuno-jejunal anastomosis are usually associated with symptoms of intestinal obstruction. The diagnosis is based on an abdominal CT scan or upper gastrointestinal series, and the treatment is usually surgical. There can be numerous other causes of abdominal pain after RYGB. Finally, chronic abdominal pain of unknown origin is reported in up to 34% of patients.(1)

How to handle the treatment?

If an internal hernia is suspected, the patient should undergo an emergent exploratory laparoscopy (Figure 3). The patient is supine with legs apart in a trocar position permitting the exploration of the common limb from the ileo-cecal valve to the jejuno-jejunostomy, the alimentary limb, the biliopancreatic limb, and the mesenteric defects.(2, 9)

Most surgeons start by unrolling the common limb from the ileo-cecal valve.

The inter-mesenteric space can be identified by the location of the jejuno-jejunostomy; the Petersen space can be exposed by suspending the transverse colon on the right side of the alimentary limb (Video 2).

An eventual hernia can be reduced by unrolling the common limb counterclockwise from the cecum. If it is not the common limb that is incarcerated, the alimentary limb can be unrolled from the gastric pouch to the jejuno-jejunostomy and the biliary limb from the Treitz angle to the jejuno-jejunostomy.(2) If the vascularization of the incarcerated bowel segment is doubtful, indocyanine green fluoroscopy may help to determine whether resection is necessary. The mesenteric defects should then be closed by non-resorbable sutures (Figure 3). The presence of chylous fluid can be an indicator of spontaneously resolved internal hernia, as the twisting of the herniated limb is accompanied by a blocking of the venous and lymphatic circulation, resulting in lymphatic engorgement. All mesenteric defects must be systematically closed, even in the absence of an internal hernia, as recurrence is described in up to 14% of patients who did not undergo closure of one of the defects.(10)

In conclusion

Dos:

- have a high index of suspicion of internal hernia

- use the CT scan generously

- a high clinical suspicion and positive CT signs or a SWELL score > 2 should prompt emergent exploratory laparoscopy

- consider exploratory laparoscopy even when abdominal CT scan shows no pathological finding if symptoms persist

- systematically explore and close all mesenteric defects

Don’ts:

- underestimate patients with subacute abdominal pain after RYGB

- discharge patients without an abdominal CT scan, if available

- delay the diagnosis

Reviewed

Sarah Peisl, Junior Editor, and Beat Schnüriger, Senior Editor.

- Fry BT, Finks JF. Abdominal Pain After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: A Review. JAMA Surg. 2023;158(10):1096-102.

- Collard MK, Torcivia A, Genser L. Modalités de prise en charge laparoscopique des hernies internes après bypass gastrique Roux-en-Y. Journal de Chirurgie Viscérale. 2020;157(5):433-8.

- Stenberg E, Szabo E, Agren G, Ottosson J, Marsk R, Lonroth H, et al. Closure of mesenteric defects in laparoscopic gastric bypass: a multicentre, randomised, parallel, open-label trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10026):1397-404.

- van Berckel MMG, Ederveen JC, Nederend J, Nienhuijs SW. Internal Herniation and Weight Loss in Patients after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Obes Surg. 2020;30(7):2652-8.

- Ende V, Devas N, Zhang X, Yang J, Pryor AD. Internal hernia trends following gastric bypass surgery. Surg Endosc. 2023;37(9):7183-91.

- Nawas MA, Oor JE, Goense L, Hosman SFM, van der Hoeven E, Wijffels NAT, et al. The Diagnostic Accuracy of Abdominal Computed Tomography in Diagnosing Internal Herniation Following Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2022;275(5):856-63.

- Giudicelli G, Poletti PA, Platon A, Marescaux J, Vix M, Diana M, et al. Development and Validation of a Predictive Model for Internal Hernia After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass in a Multicentric Retrospective Cohort: The Swirl, Weight Excess Loss, Liquid Score. Ann Surg. 2022;275(6):1137-42.

- Tustumi F, Pinheiro Filho JEL, Stolzemburg LCP, Serigiolle LC, Costa TN, Pajecki D, et al. Management of biliary stones in bariatric surgery. Ther Adv Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;15:26317745221105087.

- Kollmann L, Lock JF, Kollmann C, Vladimirov M, Germer CT, Seyfried F. Surgical treatment of internal hernia after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass - impact of institutional standards and surgical approach. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2023;408(1):318.

- Zaigham H, Ekelund M, Regner S. Long-Term Follow-up and Risk of Recurrence of Internal Herniation after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Obes Surg. 2023;33(8):2311-6.